Sitka at War

First published in the 2010 Sitka Harbor Guide

Unless you’re a fish, Sitka is a remarkably peaceful place.

But on Dec. 7, 1941 — and in the days and months thereafter – Sitka poised on the brink of world war. Soldiers and sailors scanned Sitka Sound and beyond and manned powerful shoreside batteries to blast enemy ships miles out at sea. Armed spotter planes flew over the Gulf of Alaska, searching for a Japanese fleet expected to invade first Alaska, then the rest of North America.

But on Dec. 7, 1941 — and in the days and months thereafter – Sitka poised on the brink of world war. Soldiers and sailors scanned Sitka Sound and beyond and manned powerful shoreside batteries to blast enemy ships miles out at sea. Armed spotter planes flew over the Gulf of Alaska, searching for a Japanese fleet expected to invade first Alaska, then the rest of North America.

Six months later, the Japanese Navy bombed Dutch Harbor in Western Alaska. They seized the outermost Aleutian Islands, Attu and Kiska. Sitkans could well imagine they were living on the front lines of World War II.

Some war historians believe that the Japanese attack on Alaska was purely a diversionary tactic, but not Sitkan Matt Hunter. The U.S. Naval victory at Midway Island in the central Pacific tipped the war heavily toward the U.S., and the Japanese Navy never fully recovered. But, says Hunter, that victory does not make Alaskan fears of Japanese attack groundless.

“There were these two attacks, and the bigger force was going against Midway,” Hunter said. “But the Japanese also wanted to get a toehold in Alaska. (Some historians) talk about it as though (the attack on Alaska) was a diversion. But I have read that it was probably not a diversion, but a parallel thrust. (The Japanese) had an aircraft carrier and an invasion force that went to Alaska that, otherwise, might have affected Midway.”

A high school math and physics teacher, Hunter is a lifelong Sitkan. He was born at Mt. Edgecumbe Hospital on Japonski Island, itself first built as a Naval facility. He grew up with rumors of underground hospitals built like downward skyscrapers underneath the Causeway, a string of small islands the Army connected in order to place guns there. By middle school, he rode his bike all around the area, finding pillboxes hidden in the woods. By high school he was working with an archeologist studying old WW II radar facilities atop Harbor Mountain.

At the ripe young age of 27, Hunter has become a leading expert in the remains and relics of WWII Sitka, and a tireless advocate for their preservation. He hosts the website www.sitkaww2.com. He has given presentations and guided tours to community groups interested in Sitka’s wartime legacy – the Sitka Historical Society, the Sitka Conservation Society, Alaska State Parks, Sitka Trail Works and the Sitka Maritime Heritage Society. The result has been the creation of Alaska’s newest state park, Fort Rousseau State Historical Park.

At the ripe young age of 27, Hunter has become a leading expert in the remains and relics of WWII Sitka, and a tireless advocate for their preservation. He hosts the website www.sitkaww2.com. He has given presentations and guided tours to community groups interested in Sitka’s wartime legacy – the Sitka Historical Society, the Sitka Conservation Society, Alaska State Parks, Sitka Trail Works and the Sitka Maritime Heritage Society. The result has been the creation of Alaska’s newest state park, Fort Rousseau State Historical Park.

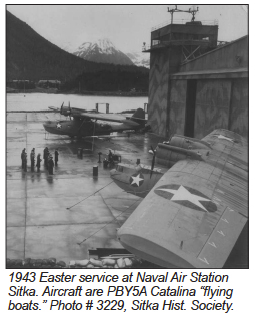

Through letters and phone calls from the veterans who manned artillery, who ran bulldozers and operated mountaintop radar stations, as well as from his research, Hunter has learned the story of WWII Sitka. “Sitka was the first operational base in Alaska,” Hunter explained. “At the time of Pearl Harbor, it was a commissioned Naval Air Station, whose construction had started in 1939.”

In the 1930’s, the Navy was given the job of drawing up plans to defend Alaska and the Pacific Region in general. Naval Air Stations were constructed at Sitka, Kodiak and Dutch Harbor. All three ports face the open sea. They were to defend the Gulf of Alaska. “The Pacific itself was to be guarded by a triangle,” Hunter said, “stretching between Alaska, Hawaii and the Panama Canal.”

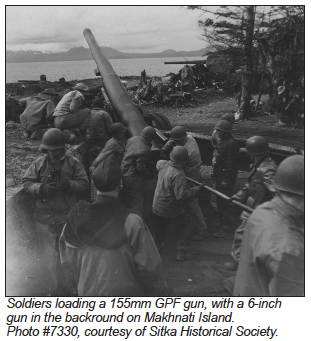

Over several years, before and after Pearl Harbor, a very elaborate coast defense system was developed. Large guns that could shoot ten or more miles out to sea were deployed around Sitka Sound – Shoal’s Point on Kruzof Island, Biorka Island and on the Causeway. Lookout towers with powerful 60-inch searchlights were placed all around the sound and, by triangulating their sightings, could pinpoint the position of a ship and the speed and direction in which it was moving. This information was relayed to the highly accurate guns, which operated in two-gun batteries. Radar was used to shoot in fog.

“A good team could get four shots a minute — that’s eight shots per battery,” says Hunter. “They would shove an 85-lb shell in, throw three bags of powder behind it, shut the breach — they would fire the gun, then put out a blast of compressed air to blow out any residue and repeat the task. You have 15 seconds to aim, fire, reload, get ready to aim and fire again — every 15 seconds. It’s unbelievable that they could do that.”

“A good team could get four shots a minute — that’s eight shots per battery,” says Hunter. “They would shove an 85-lb shell in, throw three bags of powder behind it, shut the breach — they would fire the gun, then put out a blast of compressed air to blow out any residue and repeat the task. You have 15 seconds to aim, fire, reload, get ready to aim and fire again — every 15 seconds. It’s unbelievable that they could do that.”

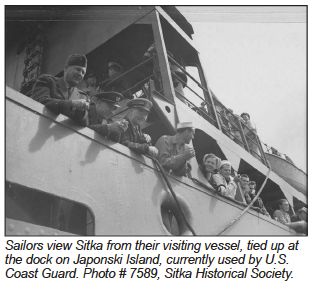

At the height of the preparations, Hunter estimates that up to 8,000 soldiers, sailors and aviators were stationed in Sitka, along with a few hundred private contractors and a contingent of Marines. This, while the population of town was only 2,000.

But the big guns never had to be put into action. Determined U.S. resistance in the Aleutians and the U.S. victory at Midway put Sitka beyond Japan’s grasp. Sitka’s main role for the war became as a trans- shipment base for men and supplies moving to the Aleutians.

Still, the big guns pointed out to sea throughout the war. Hunter talked to a veteran living in Mississippi, Cpl. Ted Gutches of Battery A of the 266th Coast Artillery at Shoal’s Point. The corporal had spent a rainy winter in Quonset huts and tents and collecting rainwater to drink.

He told Hunter where the guns were located and Hunter went out to look for remains. In fact, Hunter took the long boat trip 10 times before he finally located his prize buried under a foot of sand and spruce cones. Hunter sent photographs of his find to Gutches in Mississippi.

“There’s an exciting feeling when you find something and you know that there’s a story behind it, but you don’t know what the story is,” Hunter said. “That moment of discovery is awe-inspiring and motivates you to research and find out that and other stories. When you talk with someone who spent his early 20s defending your town from the enemy and then discover the gun emplacements and Quonset huts he left behind, there is an emotional connection that brings the past to life. It’s a personal connection that becomes part of who you are.”

Will Swagel is the publisher of the Sitka Harbor Guide and the Sitka Soup. A 29-year resident of Sitka, he has written for various regional and national magazines.